The Rock Art: Deep Call of the Sahara

c. 8000–c. 2000 BCE

While the last Ice Age covered the Northern Hemisphere with glaciers, the northern half of the African continent was quite arid. As that period came to an end, beginning about 12,000 years ago, rains came to north Africa, transforming the arid landscape into a grassland with rivers and trees. Small animals—foxes, anteaters, antelopes, jackals, and donkeys—gradually moved into the newly green area, followed by crocodiles, hippopotamuses, lions, giraffes, and elephants. The region’s buffalo, with their huge curved horns, were dwarfed by aurochs, a species of enormous wild cattle that is now extinct. Humans followed the migrating animals into the green Sahara. From about 8000 BCE, varied populations lived in the mountainous regions that now are encircled by desert sands, and their artists left images of animals, humans, and supernatural beings on the walls of rock shelters, canyons, and cliffs. About 4,000 years ago, the climate changed again, and most of these early populations left the region. As the rains disappeared, the Sahara became, once again, the world’s largest desert.

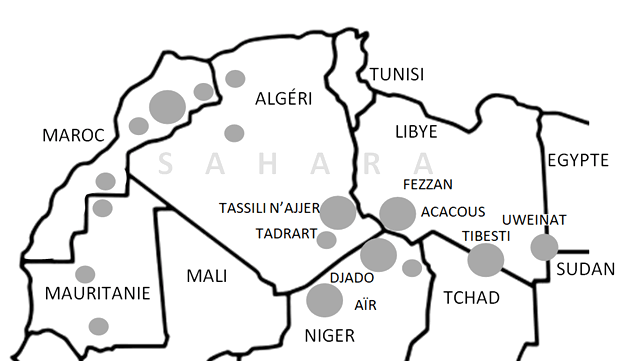

Map of the locations where the rock paintings and rock engravings were found.

LARGE WILD FAUNA STYLE RELIEFS

Early hunters carved, scraped, and polished thousands of petroglyphs into rock surfaces across the Sahara. Unlike European cave paintings of the Paleolithic period, which are deep in underground caves, the rock art found in North Africa and elsewhere on the continent appears in shallow rock shelters and on stone outcrops above ground. The ancient rock art of the Sahara that depicts in low relief the large animals then roaming the landscape is described as the Large Wild Fauna Style, or as the Bubalus Style after a now-extinct species that lived in the region.

Images in the Large Wild Fauna Style were incised during the long period of time beginning with the human resettlement of the Sahara, and ending when these animals became scarce in the region, roughly 9000–4000 BCE. Most scholars date them between 7500 and 5000 BCE, but some specialists assign them to a shorter time span, or give them later dates. The artists rubbed deep grooves into the rock surface with abrasives or stone tools to define the contours of the animals. The technique is well illustrated in one relief of an elephant, which is almost half the size of the actual animal (Fig. 2.2); additional lines provide textures for the elephant’s ears, trunk, and eyes. Cutting into and sanding down the surfaces of the rock to create these long, continuous grooves must have been an arduous, time-consuming process, suggesting that these animals were profoundly important to the artists.

Many of the wild animals shown in the Large Wild Fauna Style rock art are naturalistic, and closely resemble the actual appearance of an elephant, buffalo, or giraffe. However, some of their features have yet to be sufficiently explained. For example, a round, pitted object appears to hang suspended from the elephant’s anus. Some observers have suggested that the object indicates that the elephant is defecating, because elephant dung helped hunters to track the animals. They believe that such images were created to master the animal’s spirit before a hunt or to celebrate a successful kill. However, most rock art specialists believe that the round object is a symbol of some kind, rather than a depiction of a physical object.

Rock carvings, especially those found in the canyons of a huge rocky plateau in southern Libya named the Messak Settafet, combine animal and human features. There are a few Large Wild Fauna Style images where shallow lines at the base of an animal head hint at a human face beneath the animal features, suggesting that the artist wished to show a human wearing a mask. However, these are rare, and composite animal-headed figures such as this hybrid being are much more typical of the Large Wild Fauna Style.

Other Large Wild Fauna Style figures have the heads of felines, or even giraffes or elephants. The most numerous hybrids in the Messak Settafet, however, merge human figures with canids (wild dogs or jackals). Hundreds of them hunt, run, dance, fight, and tumble across the canyon walls. One of the most detailed depictions uses an unusual technique, outlining the shapes with a double contour and polishing the interior surfaces.

Although most hybrid figures are found in the central Sahara, incised images of animals in the Large Wild Fauna Style are scattered across the entire desert, from the foothills of the Atlas Mountains in Algeria to the Ennedi highlands of Chad. An elephant in a modified Large Wild Fauna Style was even found on a rock that rolled into the Nile River near Aswan, at the southern border of ancient Egypt. Such similarities of style and subject matter in art that was spread across enormous distances, over thousands of years, suggest that early African populations were linked through migration patterns, and that they may have shared religious practices.

ARCHAIC STYLE ROCK ART IN TASSILI N’AJJER

While the Messak Settafet of Libya was a particularly important site for Large Wild Fauna Style images, the mountain range to its southwest, known as Tassili n’Ajjer, is the home of Africa’s most diverse rock art. Rock shelters in this region of southern Algeria are protected by overhangs, and display huge paintings that are not seen elsewhere. Their figures have circular heads with no discernible facial features, and they have thus been described as the Round Head Style or the Archaic Style. In the 1980s, archaeological research in a cave near Tassili n’Ajjer dated small versions of these faceless figures to approximately 6000 BCE. The Archaic Style thus appears to overlap in time with some Large Wild Fauna Style images.

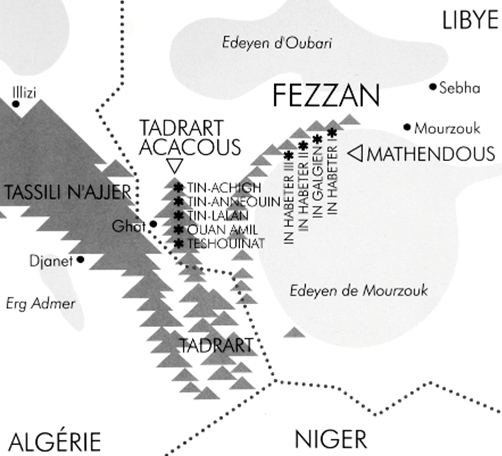

Rock art sites in southwestern Libya (Tadrart Acacus) and southeastern Algeria (Tassili N’Ajjer)

PASTORALIST STYLE ROCK ART

Tassili n’Ajjer is also the site where the greatest number of paintings in the strikingly naturalistic Pastoralist Style (also called the Cattle Style) have been found. Archaeologists have tied these paintings to the population that began to fire ceramic vessels and to domesticate wild grains and cattle in the central Sahara from 5000 to 2000 BCE. Most of their living sites have been dated to about 3500 BCE, and were abandoned about 2000 BCE. In fact, the Pastoralist Style is named for the practice of cattle herding, which they had recently developed. The paintings show not only domesticated cattle, with the specific patterns of their hides and the shapes of horns, but also humans interacting in relaxed poses and using natural gestures in what appear to be scenes of daily life. People are depicted with considerable variation, but most are shown with dark skin tones. The different sizes and proportions of the people in this detail from a much larger painting from Tassili n’Ajjer indicate that they are women, men, and children. While children appear in the art of some later Egyptian tombs and Mesopotamian monuments, lifelike images of children were relatively rare in art around the world until about 2000 years ago. Pastoralist Style rock art, therefore, includes some of the world’s earliest depictions of children interacting with their families and friends. Analysis of the paints has revealed that they contain the same ochers, chalks, and charcoal as the much earlier Archaic Style paintings. In Pastoralist Style paintings, however, the pigments are bound with cow’s milk so that the food the animals produce—along with their portraits—fill the compositions. The use of cow’s milk emphasizes cattle’s importance to these communities.

Later painted and engraved images found across the Sahara are even more varied in style as well as in subject matter. Generally, as the Sahara became more arid after 2000 BCE, naturalistic paintings were replaced by figures that were more abstract. Over time, the scenes began to include men riding horses and wheeled chariots, and, later on, camels and camel-riding nomads.